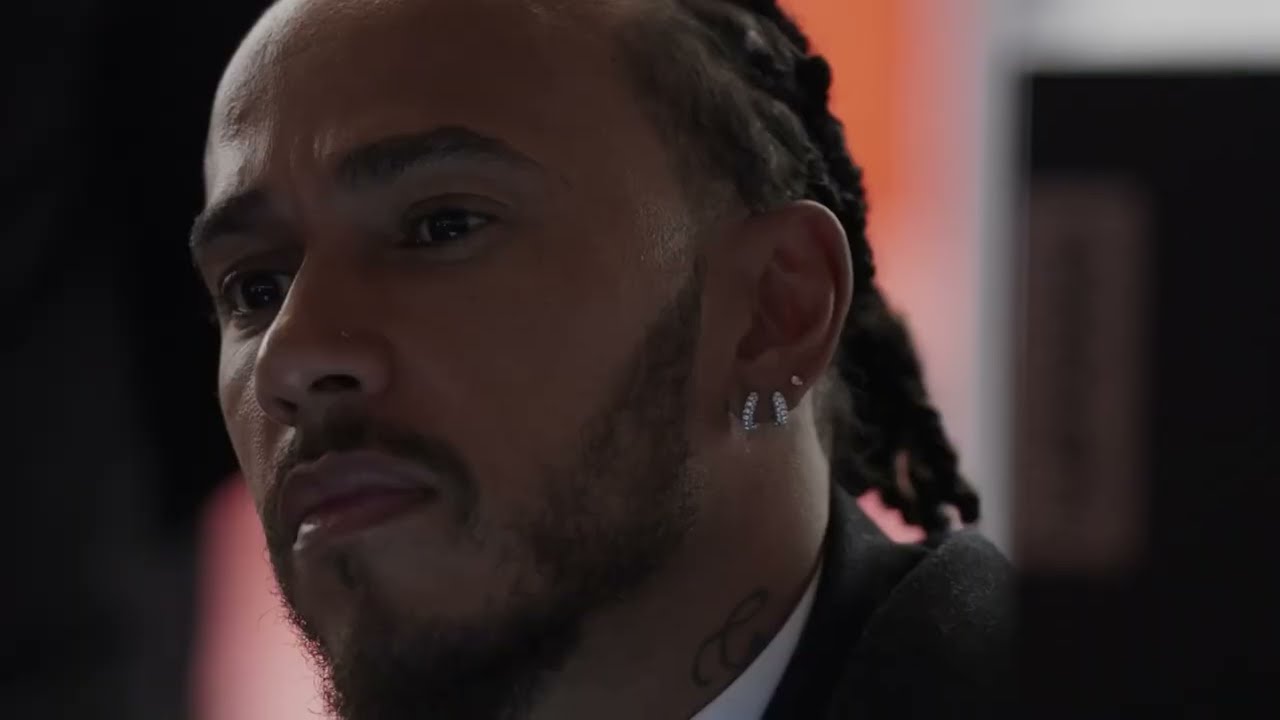

It was supposed to be a standard acclimatization session. A few installation laps, a seat fitting check, perhaps a polite wave to the cameras. But when the garage doors opened at the Circuit de Barcelona-Catalunya and the SF26 roared onto the track, something unexpected happened. Lewis Hamilton didn’t just drive the car; he dissected it. And in doing so, he sparked a high-voltage technical debate that is currently shaking the foundations of Scuderia Ferrari.

The world watched to see if the seven-time champion still had his edge. But inside the secretive halls of the Ferrari garage, the engineers were watching something far more disturbing: telemetry data that defied their predictions.

A Surgical Strike on Day One

Unlike the other drivers who spent their first morning performing basic system checks and getting comfortable, Hamilton bypassed the honeymoon phase entirely. He jumped directly into a “deep exploration phase” of the SF26’s mechanical potential. Witnesses described his approach as having a “surgical coldness.”

In just three fast laps, Hamilton was already manipulating hybrid modes that weren’t even scheduled for the initial test plan. He adapted immediately to the new 2026 “50/50” regulation—which demands perfect symmetry between the thermal engine and electrical system—with a ferocity that caught the pit wall off guard.

Where others were tentative, Hamilton was aggressive. He deployed energy regeneration modes in corners where stability is usually the priority, testing the chassis’s limits. The conclusion was instantaneous and shocking: the SF26 didn’t just withstand the abuse; it thrived on it. It was as if the machine had been waiting for a driver daring enough to handle it with such intensity.

The Clash of Philosophies: The “V” vs. The “U”

The data quickly highlighted a stark contrast between the two men now sharing the red garage. Charles Leclerc, the team’s golden boy and reference point for years, was running a meticulous program. His driving style is characterized by a “U-shaped” line—carrying high minimum speed through the apex, relying on a delicate balance and a smooth overlap between braking and acceleration. It is an effective, beautiful style, but one that operates within a narrow window. A gust of wind or a slight temperature drop can upset that perfect rhythm.

Hamilton, conversely, began defying conventional Ferrari logic. He adopted a “V-shaped” approach: shortening the rotation phase, braking later but with controlled progression, and stabilizing the platform to slam on the accelerator much earlier than expected.

This early power application shifted the center of gravity to the rear axle, generating immense traction out of slow corners. In the telemetry room, the graphs spiked. On the exits of Turn 3 and the final chicane, Hamilton was finding time chunks that Ferrari engineers hadn’t considered viable. He wasn’t just driving the car; he was widening its operating window.

The “Taboo” Question

This is where the story shifts from a sporting update to a potential internal crisis. For three seasons, Ferrari has designed cars that are extremely responsive but temperamental—machines tuned to the razor-thin preferences of Charles Leclerc. They were fast when the stars aligned, but fragile when conditions changed.

But as the engineers stared at their screens, a new school of thought emerged. The SF26, under Hamilton’s direct influence, was showing itself to be an adaptable, universal weapon.

This raised an uncomfortable, almost taboo question within Maranello: What if the car was not built for Charles Leclerc, but for someone like Lewis Hamilton?

It sounds paradoxical. The car was developed based on years of feedback from Leclerc. Yet, the newcomer unlocked its true potential by ignoring that feedback and applying his own physical and dynamic principles. The realization has put Ferrari’s entire operating model in check. Some technical staff are now quietly asking if they have been unconsciously limiting the car’s development by focusing on a single reference point.

Leclerc on High Alert

For Charles Leclerc, the Barcelona test was a wake-up call. It wasn’t a hostile takeover—Hamilton is too experienced for petty garage politics—but it was a “centrifugal force” that shifted the team’s gravity.

Leclerc is known for his speed, but for the first time, he is sharing a garage with a driver whose influence transcends lap times. Hamilton brought structure, technical authority, and a race-reading ability that resonated instantly with the mechanics.

The change was subtle but palpable. There were longer silences in the box. Engineers lingered a few seconds longer on the data streams from Car 44. Hamilton’s feedback began to carry its own weight, independent of established hierarchies.

Leclerc, usually diplomatic, began showing signs of tension. His conversations with race engineers grew longer and more urgent. He started experimenting with setup changes, driven by a sudden need to regain an advantage that, until recently, seemed guaranteed. He knows that this is no longer just about beating a teammate; it’s about survival. He has to reinvent himself from the “future of Ferrari” to a leader who can hold his ground against the most successful driver in history.

A New Era, A New Identity

The rivalry at Ferrari is not open warfare; there are no shouting matches or on-track collisions yet. It is a silent, psychological pulse. Hamilton exerts pressure simply by existing and executing with damaging precision.

As the tests concluded, the narrative had irrevocably changed. The SF26 is no longer just Charles Leclerc’s car. It has proven to be a flexible platform that mirrors the soul of the driver behind the wheel. And right now, that reflection looks a lot like Lewis Hamilton.

The big question in the paddock is no longer whether Leclerc is fast enough. The question is whether he can withstand the hidden pressure of a teammate who doesn’t need to prove anything to anyone. The SF26 has yet to win a race, but it has already claimed its first victory: it has forced Ferrari to look in the mirror and question everything they thought they knew about their own technical identity.